New writing

Walking in South Wales, an extract

Monkey puzzle

South Wales is a region of mountains, rolling valleys, craggy hills and mists. It is also a wonderful place for walking on Drovers' ways and ancient paths. The ways used to carry all the traffic of people and animals to market and beyond. Cattle trains half a mile long would comprise hundreds of animals, minded by men on horseback, chased and controlled by small sharp collies. The ways are punctuated by Scot's pines – three planted together signalled a hostelry; and by prehistoric standing stones that seem to be endowed with a certain mystic quality. Who placed them there? When, and why?

A way over the Eppynt Hills leads you to one of my favourite standing stones, Maen Richard, at a junction of three communities and a crossroads of five ways. On a clear day there are views south to the Brecon Beacons, and east to the Black Mountains. Last week, on a misty autumn morning, I visited it again. High on the ridge of the hills it stands, about 1.5 metres high, and it retains its gentle sense of magic.

But there was another stone I wanted to see, the Whetstone, which lies on Hergest Ridge near Kington, along Offa's Dyke, the great path which runs the length of the Welsh-English boundary. This stone definitely has mysterious qualities; it was said to move around from time to time but, more prosaically, it was also used to sharpen the swords of border knights. And around the stone lies a Victorian race course. It was built in 1825 and was for twenty years the home of local racing, enjoyed by local farmers, squirearchy, and gentry.

The day I went to visit the Whetstone was autumnal, misty. Trees glowed softly, amber and gold. There was the great stone, huge, perhaps two metres long, lying, not standing, and set like a tomb in the bracken.

The mist was dense but the edge of the race course was clear in the bracken: a pathway of perhaps 4 metres wide, well cropped as if still kept for racing – the 2.30 Hergest Handicap Gallop perhaps. One could almost conjure the throngs of people in full Victorian dress, drinking and swearing, wagering on the outcome as horses galloped round the elliptical one-mile course.

As I walked towards the centre of the race track a strange form emerged from the waves of mist, like a mesh of masts of pirates' galleons. The shape appeared then faded away, as if it were riding ocean waves. Nearing, I saw the masts transform themselves to a clump of nine dark green trees, quite carefully planted in the middle of the race course. Why are they there? Who planted them? Was it a joke? For they are araucarias, monkey puzzle trees, normally associated with suburban gardens, though they come from mountainous Chile. There they were considered sacred. Perhaps that is why, in the soft gray mist, their statuesque form seems so ghostly. Are they lucky charms? Or did I hear the sound of thundering hooves?

2nd November 2016

The divided village

I used to live in a small village in South Wales in a stone built cottage that sat beside the 14th century church and had views down the length of the valley towards the Brecon Beacons. I couldn't see the Brecon Beacons from there, but the village was open, and the green hills folded away towards the south.

When I arrived, there was not a single building less than 100 years old. The church I have mentioned. The chapel – for there are always both- was from the mid nineteenth century. Some of the farms were hundreds of years old, others younger. There was an old barn, stone built too and a cluster of cottages with inglenook fireplaces and tiny wooden clad stone staircases.

I lived there for nearly twenty years; my daughter was a baby when I went there, and she – a Londoner – learned the joy of wide open spaces, the seasonal rhythm of sheep and daffodils. It was not a particularly pretty village, but its buildings curved pleasingly along the edge of the Eppynt hills, falling past the church and the village hall towards a small but sometimes tempestuous stream. The heart of the village was open, and accepting. People chatted over walls, children played in the street. Not quite an idyll but charming and comfortable in the deep green valleys. So life continued for ten years or so, but then I left, with warm memories and good friendships.

Last night I went back for the first time in several years. It is now known as the 'divided village'.

What had happened was that one of the farmers, call him Jones, applied for planning permission to build a three houses in the empty water meadow lying in the centre of the village. Adjacent to my former cottage. He had tried some years earlier to build a single bungalow but many residents objected and it was thrown out. This time permission was granted and the village was sharply split between those who felt it was the farmer's own business; and those who feared the village would be changed utterly. People who had been friends ignored each other, badmouthed each other. There was fisticuffs on one occasion. Friendships disintegrated and hostilities took root. And now two large wooden modern houses dominate the centre of the village, like newly landed aliens.

In riposte the people with old cottages who used to share the open view down the valley – have planted trees and hedges. A six foot hornbeam hedge against one wall, a tall fence of pleached limes perhaps 10 foot high in another garden; the new houses close off my old view and to hide them the people who live there now have built a 12 foot high wooden fence.

The once open core of the ancient village is now dominated by the high hedges, so now there are only narrow glimpses of the valley beyond. It reminded me of a maze, so narrow have the vistas become. The rolling hills of the open valley around are still beautiful; the night sky was brilliant with stars; and the sheep are unconcerned, but I'm glad I no longer live there.

October 2016

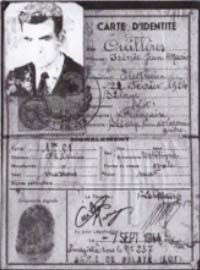

A cache of letters, a family history, a forgotten battle – IN my house in rural southwest France, I found over 100 old letters, crammed into corners in the loft and the cellar – which tell of day-to- day life in a valley in the Lot over a period of 35 years, the earliest dating from 1915 and the final ones from the 1950s. They cover three generations of the family Ouilleres, who owned the house before I bought it. They were farmers, vignerons, and also managed the estates and chateaux for the local but absentee aristocracy, and the letters reflect their business, their servant-master relations with the aristocrats for whom they worked as well as domestic life - marriages, deaths, and illness.

A cache of letters, a family history, a forgotten battle – IN my house in rural southwest France, I found over 100 old letters, crammed into corners in the loft and the cellar – which tell of day-to- day life in a valley in the Lot over a period of 35 years, the earliest dating from 1915 and the final ones from the 1950s. They cover three generations of the family Ouilleres, who owned the house before I bought it. They were farmers, vignerons, and also managed the estates and chateaux for the local but absentee aristocracy, and the letters reflect their business, their servant-master relations with the aristocrats for whom they worked as well as domestic life - marriages, deaths, and illness.

A blend of business and personal, the letters provide a rich narrative thread for the history of those years, through domestic and private events to the years of the Second World War, the years of Vichy government, and the occupation by Germany after 1942. They culminate at the end of the 2nd World War in the drama of the Resistance, and the death of oldest son of the family in a battle at the Pointe de Graves in early 1945. The book will thus be a mix of the personal and the historical, using the letters as a framework, and will be published in 2017. Read more

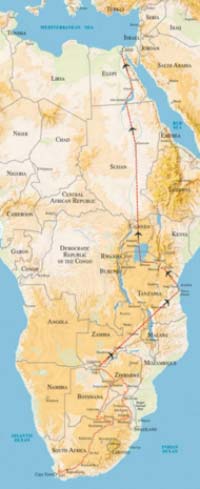

From the Cape to Cairo: Two journeys through Africa – ten journeys through history

Towards the end of the Second World War my parents made a journey overland from Cape Town to Cairo. The diaries they kept then provide an intriguing snap shot of the state of the spine of Africa. From South Africa to Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo; on to Tanganyika, Kenya and then, north of Lake Victoria, Uganda, Sudan, and Egypt. I am re-tracing the footsteps as along a 'spine' of Africa after a lapse of around seventy years. It is not the same journey; the names of some of the countries are different – although most of the boundaries are not. The transport possibilities are no longer the same; the Nile steamer has gone, but there are trains and new roads. And the politics of the Sudan and South Sudan – the one place where boundaries have changed - and in northern Uganda mean travel is unsafe, whereas in 1945 these were deemed civilised places.

Towards the end of the Second World War my parents made a journey overland from Cape Town to Cairo. The diaries they kept then provide an intriguing snap shot of the state of the spine of Africa. From South Africa to Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo; on to Tanganyika, Kenya and then, north of Lake Victoria, Uganda, Sudan, and Egypt. I am re-tracing the footsteps as along a 'spine' of Africa after a lapse of around seventy years. It is not the same journey; the names of some of the countries are different – although most of the boundaries are not. The transport possibilities are no longer the same; the Nile steamer has gone, but there are trains and new roads. And the politics of the Sudan and South Sudan – the one place where boundaries have changed - and in northern Uganda mean travel is unsafe, whereas in 1945 these were deemed civilised places.

In seventy years, a lifetime, three generations, the changes along the spine have been profound. Much has been written of the political history of Africa but my work will reflect too on development and the lives of ordinary people over this momentous period in African history, informed by the eye of a professional and experienced development economist.

Follow my travels on my blog – Two journeys through Africa - ten journeys through history!